This summer has seen a record-breaking heatwave; in this post, I will discuss why hot weather is not all good news for the sun-loving Dragonfly.

We often associate dragonflies with summer and sunny, dry weather. It’s logical to think that such hot days are beneficial to dragonflies. However, the heatwaves we are experiencing in Britain because of climate change are anything but favorable. Such long periods of hot, dry weather can have a detrimental impact on dragonfly wetlands. Lack of rainfall and increased evaporation (because of the heat) can cause a fall in water levels or complete desiccation. This leads to the death of any resident aquatic dragonfly larvae. The BDS (British Dragonfly Society) has specific concerns about some of our more vulnerable species, such as the Azure Hawker.

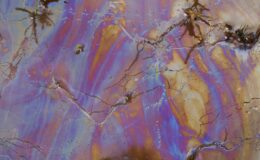

Dried pond at Parc Slip Nature Reserve. Tragically such desication leads to the death of any resident aquatic dragonfly larvae

The past couple of years have seen recorders in Scotland witnessing the complete drying out of several known Azure Hawker breeding pools, resulting in the generation’s loss of larvae that were resident there. An important goal for the managers of wetlands sites is now to increase the resilience of their sites to periods of drought.

There are some species, such as the Emperor Dragonfly, that are responding positively to our warming climate by expanding their range north into areas that were too cool for them historically. Whether such dragonfly expansions become more common, only time and diligent recording will tell. What is becoming clearer is that our wildlife will have to adapt to the challenges of global warming. Some species will thrive; others may hang on, while others will sadly perish.

Although some species, such as this female Emperor Dragonfly, appear to be expanding northwards, they still need healthy wetlands on which to breed and lay eggs

On a recent visit to Parc Slip Nature Reserve, South Wales – it shocked me to find a pond, so important for the smaller dragonfly species, such as the Common and Rudy Darter, practically dried up. A week later, I revisited this pond, only to find it completely dried up.

Lack of rainfall and August temperatures above 30 degrees had a detrimental impact on dragonfly ponds

I remembered how, a week previously, the shallow pools attracted a frenzy of dragonfly activity as mating couples competed for the few remaining dregs of water on which to deposit eggs. It broke my heart to think that all their efforts of passing on their genes and ensuring the survival of their offspring would result in nothing more than sunburnt, desiccated eggs, frying on dried, cracked mud. ‘Dust to dust, ashes to ashes’ is the inevitable fate of all that lives and a brutal acceptance of old age and the ravages of time. As sure as night follows day, we accept this. However, it seemed perverse and unjust to apply this law to what should have been for many dragonflies a lifeline for their progeny.

There was a frenzy of dragonfly activity as mating couples deposited eggs on the last remaining dregs of water.

Sad to think that within a week the pool had dried up, leaving little hope for the deposited eggs.

Male Common Darter leading female by the scruff of the neck.

The female lowers her abdomen and deposits eggs. In pogo stick fashion, the male, then bounces her up and down into the water in order to disperse the eggs.

After dispersing the eggs, the couple then look for another suitable spot on which to deposit more eggs. This cycle is repeated for quite some time.

A protruding, dried grass stem, makes an ideal perch from which the Common Darter can survey his territory, fend off rival males and/or see females with which to mate.

Males will often return to the same perch.

Like all dragonflies, Common Darters are strong fliers, their small size making them particularly nimble and acrobatic!

Dragonflies are not the only ones affected by heatwaves; birds, mammals, and other insects, such as bumblebees, suffer from dehydration and heatstroke. Bumblebees and butterflies among those most affected. There have been reports of rare purple hairstreak butterflies venturing down from the tops of oak trees to ponds to get moisture. Across the UK, there is concern the heatwave will have scorched plants that these insects feed on and killed young caterpillars, which could cause dramatic declines in some species.

Bumblebees will also be badly affected, said Dave Goulson, a professor of biology at the University of Sussex. They are relatively large and have furry coats which are adaptations to living in cool conditions. In 40C heat, they could not forage. “They overheat in very warm weather and simply cannot fly–imagine trying to flap your arms 200 times per second while wearing a fur coat,” said Goulson. They usually have some food reserves in their nest, so might survive for a few days, but could die because of prolonged periods of heat.

During the heat of mid-day, this Red-tailed Bumble finds a shady, sandy damp patch on which to settle and cool down. When it’s very hot, such cool habitats provide ideal micro climates for many insects.

Animals such as reptiles and insects, which are ectotherms, are also badly affected because they cannot control their body heat.

Leave a Comment