I know of many photographers who have no qualms about killing and freezing insects in order to gain more control over macro shots. While I admire their skill as photographers, I question their methods and not collect insects purely for the sake of photography. Any environmentally conscious photographer has a responsibility to treat their subjects with respect. Insects are living organisms and their well-being should come before any photographic consideration.

Of course, it should be recognised that there may be genuine scientific reasons for killing and preserving insects, but let’s not confuse this with killing for purely photographic, artistic or aesthetical reasons. The scientific argument has been persuasively explained in some detail by the entomologist Piotr Nasrecki in his blog post: Involuntary Bioslaughter and Why a Spider is Dead.

Nasrecki makes an interesting case for euthanizing and preserving insects in museum collections but fails to address whether insects have consciousness and a capacity to experience pain. Unfortunately, the suffering of invertebrates, even for scientific purposes, is not considered with the same level of seriousness as that of mammals. They are not given much moral consideration nor regarded as possessing any individuality, but are rather perceived as prototypes of their species. The treatment of vertebrates may be far from perfect, but at least we no longer doubt they can feel pain. Thus, research on vertebrates often (depending on the country) has to be approved by an ethics committee. This is not the case for insects. Research ethics in entomology are mainly concerned with the environment and species, but not with insects as individuals. For a more detailed explanation go to the article: Entomology And The Ethical Treatment Of Insects.

Photograph from Alfred Wallace Collection, at National Museum of Wales, Cardiff.

It was common practice for Victorian collectors, such as Alfred Wallace and Charles Darwin, to kill and preserve insects. While such practices have led to important scientific theories and discoveries, can the killing of insects be justified today, especially with so many curatorial alternative methods, such as photography, painting and 3D modelling?

Take for example a dragonfly specimen, pinned, mounted, framed and preserved. The dragonfly may be a darter, Ruddy Darter, which, if alive, would have the most brilliant red abdomen. No doubt such a specimen would have been part of a Victorian entomologist’s collection. Such a preoccupation with killing, collecting, tagging and then neatly cataloguing specimens inside wooden framed cabinets had little regard for the ecological importance of such insects, let alone their well-being. Some species have become sadly endangered and we have museum rooms filled with desiccated samples. No preservatives known to science are going to keep the intense colours that once defined these once-living organisms. Such tragic abuse of insects is sadly all too common with our treatment of animals; failing to consider just how unique, precious and fragile life is. The taxonomy of living organisms may be of benefit to our understanding of plants and animals, but it cannot preserve the wonder of life anymore than capture its living essence.

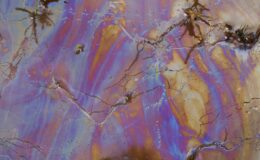

Preserved specimen of Darter. The abdomen should be bright red (see image below).

No preservatives known to science are going to keep the intense colours that help define this dragonfly.

Like all dragonflies, Common Darters are strong fliers, their small size making them particularly nimble and acrobatic!

My photograph captures their living essence far better than any stale, dried specimen.

Scientists may assure us that there is no substitute for the collection of physical specimens. They may point out that museum collections are priceless not only because of their role in scientific discoveries, but for igniting the fascination with the natural world in future generations of researchers, artists, and conservationists. However, should we not treat insects as if they might have some consciousness and as sentient beings, capable of experiencing pain, even if it is at a low level? Do not scientists have a moral duty to consider and use other methods of documentation, such as photographs, paintings, sound recordings, non-destructive DNA samples, 3D computer models?

There are catalogued electron micrographed 3D scans of many insects now, making them available to the public if you know where to look. Perhaps worth a thought as a more ethical process of displaying insects. Especially considering you can print at any scale! An Austrian artist, Klaus Leitl has crafted 3D printed replicas of many insects. Modelling the insects at a 30:1 scale enhances details and allows for their beauty to stand out. Could 3D scanning transform entomology? Scientists are already using 3D scanning technology to create realistic models of insects. The Smithsonian Institute in Washington DC is currently undergoing a major 3D scanning project, gathering digital versions of its entire 137 million-piece collection. This will enable the public, schools and collages to access accurate scans of its collection from practically anywhere in the world without risking damage to the original. You can find links to this ambitious and exciting area of 3D printing at the end of this post.

3D printed Mayfly by Klaus Leitl

Turning to my specialism and a more traditional area of macro photography, I’d like to consider a favourite butterfly of mine, the Grizzled Skipper. This butterfly, which, like many insects, has declined drastically since 1984. There is scant photographic evidence of its presence in Wales, apart from photos of a dried specimen on the British Lepidoptera web page. Chris Lewis captured an image in Merthyr Mawr on 20 May, 2011. The butterfly is dissected into parts: the head, antennae, legs, wings, abdomen and female genitalia. These analytical studies are reminiscent of the dried butterfly specimens seen in museums or hanging as framed interior decorative emblems in peoples’ homes.

Dried Specimen of female Grizzled Skipper; photograph by Chris Lewis

In contrast, the ecologist Dr Mary Gillham had posted a picture of a pair of Grizzled Skippers mating on bracken. She had taken the photograph in Candleston Burrows way back in May 1984. Dr Gillham explored South Wales, recording all the species she found, sometimes for personal interest, other times for educating students and sometimes to record what species and habitats were present to provide evidence for protecting an area.

A pair of Grizzled Skippers mating; photograph Dr Mary Gillham

I’ve always been more interested in the value of having a personal and direct experience as opposed to learning from an empirically scientific description. Much like Dr Gillham, I like to photograph insects within their natural habitat and not as separate, caged entities. I question our western obsession with analysing and trying to explain everything, which can so often result in killing off any sense of awe, beauty, joy and wonder. “Do not all charms fly at the mere touch of cold philosophy”, questioned the poet John Keats. Dr Gillham had to seize that moment of synchronicity, of two skippers coming together, mating and hopefully passing on their genes to the next generation. It was a magical and ephemeral moment with no need for any verbose explanation. Like telling a joke. It should not need clarification. Either it is funny or not? The same holds true with beauty. You either agree with Keats, wax lyrical about ‘truth being beauty and beauty truth’ or else you think such reactions are too subjective and self-indulgent.

Grizzled Skipper at Merthyr Mawr Warren, Wales.

Merthyr Mawr is one of the few remaining strongholds in Wales for small, self contained colonies of Gizzled Skipper butterflies.

I’ve visited this site yearly between May and June since 2016.

Let’s make another comparison, this time of a stag beetle. The first image is a photo of a preserved specimen. Let us now compare this with a watercolour by the Renaissance graphic artist Albrecht Dürer. Which one do you think captures the essence of the stag beetle more successfully? It is clear as daylight that Dürer captures the living qualities of the beetle. See how the legs bend under the weight of the beetle’s body and how majestically he stands with mandibles raised as if to ward off any competing males. See how proudly he shows off his virility to entice any female. Dried specimens may be carefully staged and contorted into artificial, so-called natural positions, but the fact they are dead deprives them of any sense of anima, soul, living essence, life force. They are as animated as the dead parrot in the Monty Python sketch.

Left: Preserved Stag Beetle Specimen / Right: Albrecht Dürer, watercolour of Stag Beetle, 1505

One can research an insect’s biology and behaviour profusely. Through dissections, one may come to a better understanding of their form and structure. But no preserved specimen can ever be a substitute for observing, experiencing, and, if lucky, photographing or painting their presence. Why would someone choose to kill and preserve an insect? There is so much more to discover from observing their behaviour. Killing and preserving an insect extinguishes their animated spark forever.

‘Let Nature be your tutor’, exclaimed the poet William Wordsworth. Go out and listen to the song of the linnet whose trilling song is musical and pleasant. There’s more ‘wisdom’ contained in that sound than you’ll find in books (or museums, I might add). We can patiently add fact to fact, but such epistemological inventories will only take you so far. Knowledge need not come at the expense of another creature’s life, but work alongside it. As knowledge increases, so does our understanding and empathy.

Beautiful Demoiselle photographed along the river Lynher, near Callington, Cornwall.

Raising his abdomen as if ready to pounce, this male is ready for action!

A photograph is better than any preserved specimen as it not only places the insect within a habitat but also reveals its behaviour. Most striking of all, it captures some of the vibrant colour and iridescence that fade soon after death.

Enough of killing and collecting specimens! There comes a time to put away such detached learning. Stop prevaricating, grasp your camera, stuff some clothes and other essentials into a rucksack and with mixed feelings of excitement and trepidation, leave the safe harbour of your home and explore nature. ‘Fool’s gold’, a cynical inner voice may mock, reminding one that any quest inevitably ends in failure. That is the considered response of caution, that tries to rationalise everything, preventing us from taking risks. Then, a louder, more assertive voice silences this, reminding us that wary people are seldom adventurous or take risks, so how are they to know where or how our path will end? Besides, time is running out for many insects. Once gone, they are gone forever. This is the tragic fate that befalls so many endangered species. Living the moment, venturing out into nature’s unchartered territory, is all part of leaving the safe harbour that defines our selfish sense of self. Delving into the consequences of failure may be the prerogative of many skeptical, cynical people, but such thoughts are not ones to hinder any adventurous naturalist. Only by embracing the fascinating and interconnected world of insects and the small creatures that sustain our environment can we hope to find our lost city of gold, our Eldorado. Perhaps then it may dawn on us that this city is no fictitious utopia but is physically present on the very earth we stand on.

Linked References:

Involuntary Bioslaughter and Why a Spider is Dead.

Entomology And The Ethical Treatment Of Insects.

Austrian Man Creates Extremely Detailed 3D Printed Insects on Form 1+3D Printer

Could 3D scanning transform entomology?

3D Printed Life-like Insect Models raise awareness of Invasive Species

Leave a Comment