Here are my favourite 5 images of 2022. I started doing this last year and settled on 5 photos, so now that will be my standard number of images I pick out each year. With so many glorious images to choose from, it’s been challenging trying to limit my selection to just 5. The best photographs are often the ones that bring back memories. It is often said that a photograph captures a moment in time, but time is never static. All pictures tell a story. Sometimes one can tell the story and other times one has to search for it. For the photographer, the meaning is especially meaningful because it carries his/her hopes and aspirations. This is especially true for wildlife photography, where the search for a particular creature can turn into an obsession, a quest for meaning and, dare I say, redemption. This is especially the case today, where the environmental threats of global warming, pesticides, monocultures, habitat loss etc… contributing to deaths by a thousand cuts. All of which is having a devastating effect on insect numbers, with some species threatened with extinction. I marvel at the privilege of having had the good fortune to photograph such small and vulnerable creatures in their natural environment. I hope that the selected images help highlight the beauty and importance of insects and the environment in which we all depend.

In no particular pecking order:

1. Facing the Abyss.

Beautiful Demoiselle, raising his abdomen as if ready to pounce, this male is ready for action!

Olympus E-M1X with Olympus 40-150mm f/2.8 + MC-14 teleconverter – f/4 / 1/125 / 190mm / ISO 800.

Whenever I visit Cornwall, I make it a priority to spend some time by the River Lynher to photograph the most striking of damselflies… the Beautiful Demoiselle. I used the Olympus E-M1X with Olympus 40-150mm f/2.8 + MC-14 teleconverter. The minimum focus distance on the Olympus 40-150mm is 2.3 feet. (0.7m) which gives it a reasonable 1.5 maximum magnification. If you ever need more magnifying power when shooting close to your subject, then the 1.4x teleconverter MC-14 delivers frame-filling magnification of your subjects for even more dramatic close-up photography. It also extends the reach to an equivalent of 420mm with a maximum aperture of f4. A 9-blade rounded diaphragm forms the apertures; the fast aperture, rounded blades, and 420mm equivalent focal length (with MC-14) gives beautiful bokeh in the out-of-focus areas.

If you were to tell me, I would take damselfly shots with this lens, I would have questioned your sanity. But you know what? The lens performed brilliantly. It surprised me I didn’t feel the urge to go for my dedicated macro lens. I’m very pleased with this shot. No, it’s not a macro shot. But 420mm (equivalent) at 28” (0.7m) is a pretty strong close focus setting. It meant that I didn’t have to pull the 40-150mm off the camera nearly as much as subjects got smaller and closer. Indeed, it was only when I was getting extremely close to small subjects that I even wanted a macro lens. That’s what a good zoom lens should do: stay on the camera as much as possible. You use zooms for some convenience, and anything that lens does to keep you from having to switch to another lens is more convenience.

2. Last Flight

Like all dragonflies, Common Darters are strong fliers, their small size making them particularly nimble and acrobatic!

Olympus E-M1X with Olympus 40-150mm f/2.8 + MC-14 teleconverter – f/4 / 1/6400 / 210mm / ISO 1600.

This summer had seen a record-breaking heatwave. We often associate dragonflies with summer and sunny, dry weather. It’s logical to think that such hot days are beneficial to dragonflies. However, the August heatwaves were anything but favorable. Such long periods of hot, dry weather had a detrimental impact on dragonfly wetlands. Lack of rainfall and increased evaporation (because of the heat) caused a fall in water levels or complete desiccation. This lead to the deaths of any resident aquatic dragonfly larvae.

On a visit to Parc Slip Nature Reserve, South Wales – it shocked me to find a pond, so important for the smaller dragonfly species, such as the Common and Rudy Darter, practically dried up. A week later, I revisited this pond, only to find it completely dried up. I remembered how, a week previously, the shallow pools attracted a frenzy of dragonfly activity as mating couples competed for the few remaining dregs of water on which to deposit eggs. It broke my heart to think that all their efforts of passing on their genes and ensuring the survival of their offspring would result in nothing more than sunburnt, desiccated eggs, frying on dried, cracked mud. ‘Dust to dust, ashes to ashes’ is the inevitable fate of all that lives and a brutal acceptance of old age and the ravages of time. As sure as night follows day, we accept this. However, it seemed perverse and unjust to apply this law to what should have been for many dragonflies a lifeline for their progeny.

This picture is poignant, as I took it the week before the pond had dried up. It captures a flying male Common Darter, at the prime of his life, on patrol duties, looking for a mate. Photographing dragonflies in flight is challenging and difficult. However, with patience, perseverance and above all a planned approach, it is possible to take some decent captures. To capture dragonflies in flight, you must spend some time observing their flight patterns in order to predict where one will be when you press the shutter. Trying to follow a dragonfly while looking through the viewfinder is frustrating and highly futile, simply because it is far too fast! I find it far better to establish what their flight path will be so that I can focus on an area along that path before pressing the shutter at the split second the dragonfly crosses that spot.

I took the shot on an Olympus E-M1X with Olympus f2.8 40-150mm lens and 1.4 teleconverter. The 121-point all cross-type On-chip Phase Detection AF system and 18 shot burst mode, were great for capturing such dynamic shots. However, most often, no automatic focusing system is going to be quick enough to catch such fast and erratic moving subjects. As with other areas of wildlife photography, success is as much to do with watching the behaviour of your subject as much as applying a sound photographic technique.

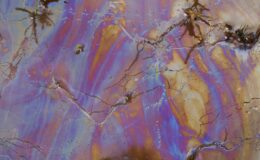

3. Mottled Beauty

Orange Tip, found early in the morning while still roosting on dandelion head.

Olympus E-M1 MarkII with Olympus 60mm f/2.8 macro – f/2.8 / 1/1000 / 60mm / ISO 400.

In April I visited Kenfig Nature Reserve and captured this image of the striking underwing patterning on an Orange Tip butterfly. This was my first image of a butterfly captured during the 2022 season.

No butterfly better symbolises the arrival of spring than the Orange-tip. They can be challenging subjects to photograph, as they will not stay still for long but like to roam the countryside tirelessly. By studying their behaviour, I have observed that they patrol a certain patch of woodland (usually along the hedgerow). So when one flutters away I patiently wait and, as sure as night follows day, the butterfly returns to the same spot. By venturing out early in the morning, I found this pristine specimen of an Orange Tip roosting on a Dandelion Head.

When resting, the undersides of the hind wing are visible and camouflage takes over as the most important form of defence. It creates a lovely lichen-like mottling from an intricate mixture of black and yellow scales on the exposed wing surfaces. Males are unmistakable, because of their bright orange-tipped wings. However, females are similar in appearance to other whites. The beautiful green mottling of the underside of the hind wing readily identified both males and females, when perched with wings closed.

4. The Not So Dingy Skipper

Dingy or beautiful? With delicate patterns and a subtle mix of contrasting greys and browns, this skipper is anything but drab!

Olympus E-M1X with Olympus 40-150mm f/2.8 + MC-14 teleconverter – f/4 / 1/1250 / 210mm / ISO 400.

The Dingy Skipper may not have the rainbow, brilliant iridescence of a Peacocks’ blazing wings. It may not ignite one’s curiosity as much as the nomadic wanderings of the Orange Tip, as it flutters past streams and meadows. Nor possess a Painted Lady’s olympian stamina as it leaves South Africa in search of our ancient Albion shores. It is mostly brown and what many people may consider a fairly dull butterfly. The type of butterfly that might scarcely divert your gaze as it fluttered past. Mostly brown and fairly drab, one might surmise. Indeed, the name Dingy Skipper suggests this butterfly is the drabbest of all British butterflies.

Despite its unfair and unflattering name, this butterfly is anything but drab. If looked at closely, newly emerged specimens possess a subtle mix of contrasting greys and browns that are quite beautiful. With the passage of time and the loosing of their scales, one would have to concede that the butterfly takes on a more uniform and drab appearance. We can see the same subtle mix of contrasting greys and browns in most things that age.

However, beauty is more than skin deep and, like all skippers, it possesses a strong, plucky character that is highly engaging. Although there is a superficial resemblance to the Grizzled Skipper, the Dingy Skipper is more likely to be confused with the Burnet Companion Euclidia glyphic or Mother Shipton Euclidia mi day-flying moths with which it often flies.

Despite the decline in numbers, the Dingy Skipper has a fairly broad distribution, its stongholds being undeniably the south-facing chalk and limestone grasslands in central and southern England. We can also see the Dingy Skipper basking on patches of bare ground, such as on sand and stones, in full sun in coastal areas of South Wales. I have a great fondness for Merthyr Mawr Warren and I’m so excited to display this photograph of a Dingy Skipper from my trip there. The sunny, sheltered sand dunes with their sparse grass sward, interspersed with patches of bare ground, provided an ideal habitat. Better still, there were also plenty of the yellow flowers of Common Bird’s-foot-trefoil (larval foodplant of the Dingy Skipper).

5. Paradise Regained

Alert and ready for action, this perching male is looking for females while guarding-off potential males.

Olympus E-M1X with Olympus 40-150mm f/2.8 + MC-14 teleconverter – f/5.6 / 1/640 / 210mm / ISO 400.

Anyone who follows my posts will know of my obsession with the Grizzled Skipper. Come May, I visit their stronghold at Merthyr Mawr Warren and have done this for the past six years. Like many butterflies, their numbers have dropped by alarming levels and every year, a sense of duty urges me to chase their elusive flight. Last year, after a long and prolonged search, I only found one Grizzled Skipper. This skipper was too far away to make a wonderful photograph, but at least it provided some evidence of its tenacious survival at Merthyr Mawr. While relieved to have seen this Grizzled Skipper, it troubled me I had seen no others. Was this the last of the Grizzled Skippers at Merthyr Mawr? This niggling thought had been burning away, etching itself in my mind. Perhaps a return to Merthyr Mawr with further sightings of this lovely and highly engaging butterfly would help relieve such fears? Perhaps even just a glimpse of its chequered wings could burnish out such insecurities?

As you can see, I was not disappointed! Not only did I spot this one… but two, then three! … Dare I say, a healthy colony of Grizzled Skippers gracing the sky with their aerial acrobatics. I had regained the paradise that seemed lost!

Leave a Comment