Butterfly Conservation’s Big Butterfly Count 2021 data shows many butterflies in decline, least among them the Small Tortoiseshell -32% down from last year’s count. Back in August, I felt fortunate to have spotted a bonanza of Tortoiseshells on a visit to Cornwall. They seemed plentiful but I suspect it was probably a case of being at the right place and at the right time. It was the height of summer with glorious weather and lots of colourful flowers to feed on. Unfortunately, back in my home in Wales, I have not had such luck with sightings. I now look back with a good degree of nostalgia to those memorable Summer days back in Cornwall.

Canon EOS 80D – Canon EF100-400mm IS II USM – f5.6 / 1/1250 / 300mm / ISO 1600

Haven’t seen many Tortoiseshells back home in Barry, South Wales but in Callington, Cornwall – they were plentiful.

The small tortoiseshell is mainly reddish-orange in colour, with black and yellow markings on the forewings and a ring of blue spots around the edge of the wings. A medium-sized, attractive butterfly, I found many in the early morning hours feeding on buddleia and other garden flowers. The males seemed very territorial, chasing each other; other butterflies and anything else that appeared in their space. They waited for a passing female with their wings held open, launching themselves at any intruders. However, unlike the closely related Peacock, they will tolerate other males in the vicinity and I saw them feeding alongside Red Admirals.

Canon EOS 80D – Canon EF100-400mm IS II USM – f8.0 / 1/3200 / 400mm / ISO 1600

I found many in the early morning hours feeding on buddleia and other garden flowers.

The population decline, especially in the south, over the last few years is particularly worrying. This butterfly has always fluctuated in numbers, but the cause of its recent decline is not yet known, although various theories have been proposed. One is the increasing presence of a particular parasitic fly, Sturmia bella, due to global warming – this species being common on the continent. The fly lays its eggs on leaves of the foodplant, close to where larvae are feeding. The tiny eggs are then eaten whole by the larvae and the grubs that emerge feed on the insides of their host, avoiding the vital organs. A fly grub eventually kills its host and emerges from either the fully-grown larva or pupa before itself pupating. Although the fly attacks related species, such as the Peacock and Red Admiral, it is believed that the lifecycle of the Small Tortoiseshell is better-synchronised with that of the fly and it is therefore more prone to parasitism.

Canon EOS 80D – Canon EF100-400mm IS II USM – f8.0 / 1/2000 / 300mm / ISO 1600

Basking in the sun, on hot rocks with wings wide open, adults rely on warmth from outside their bodies. This warmth raises their body temperature to a level that will enable them to be fully active.

Changing weather patterns and climate change are also thought to impact the availability of lush and nitrogen-rich nettles, which the females depend upon for egg laying. An earlier emergence may also be reducing the proportion of adults that go into hibernation versus those that go on to produce another brood, exacerbating any declines due to a lack of suitable nettles.

Canon EOS 80D – Canon EF100-400mm IS II USM – f8.0 / 1/1600 / 300mm / ISO 1600

Despite being a widespread and common species in certain areas, the declining fortunes of this butterfly, especially in the south, mean that this butterfly is a species of conservation concern.

The adults feed on Buddleia but they can feed on whatever nectar sources are available at that time of year, including Betony, brambles, dandelions, Devil’s-bit Scabious, Field Scabious, Greater Stitchwart, hawkweeds, heathers, Hemp-agrimony, Ivy, knapweed, Michaelmas-daisies, Primrose, ragworts, sallows, sedums, thistles, Water Mint, Wild Marjoram, Wild Pivet and Wild Thyme.

Canon EOS 80D – Canon EF100-400mm IS II USM – f8.0 / 1/4000 / 400mm / ISO 1600

The adults feed on Buddleia but they can feed on whatever nectar sources are available at that time of year.

An encounter with another male results in a pair flying in tight circles around one another, ascending as they do so, with the original male eventually seeing off his rival and returning to his territory. When a female enters the territory, however, a most curious courtship begins. In his book, ‘Life Cycles of British & Irish Butterflies, Peter Eeles gives a fascinating account:

“The male approaches the female from behind and ‘drums’ his antennae on her hindwing, making a faint sound that is audible to the human ear. The female may fly a little distance, with the male following, when the process repeats. This can go on for several hours with the couple spending a good amount of time basking together and with the male chasing off any intruding male. The female will also drop into a nettle patch and crawl for a short distance, presumably to test the male for suitability and, if he loses him, will subsequently accept the advances of a different male. Eventually, usually in early evening, the female will lead the male into vegetation, often a nettle bed within the territory, and crawl between stems with the male following and, if the male succeeds in staying with her, the pair mate and remain coupled until the following morning.”

Canon EOS 40D EF100mm f2.8 Macro USM – f5.6 / 1/250 / 100mm / ISO 400

Back on the 8 March 2014 I managed to capture this pair of mating Small Tortoiseshells.

Taken in Porthkerry Park, Barry, Vale of Glamorgan.

After the pair separate, Eales found that the female selects a preferred nettle patch in the afternoon and roosts low down within it overnight. She emerges the following morning to bask and make short flights, before laying a batch of eggs, usually between 10am and 2pm. The female may lay further batches on subsequent days, with each batch comprising between 60 and 100 eggs that can take over an hour to deposit. Plants that are in full sun and at the edge if the nettle bed are selected, with eggs laid on the underside of one of the larger leaves at the top of young nettle growth. Like many other species that lay eggs in batches, the female will occasionally lay in the presence of other females, even on the same leaf and occasionally on top of an existing egg batch.The batches themselves are untidy, with eggs laid on top of one another, as in the Peacock.

Canon EOS 7D EF100mm f2.8 Macro USM – f5.6 / 1/320 / 100mm / ISO 400

This fertilised female was captured in the process of laying her eggs. As with most butterflies – and especially those that lay large batches of eggs – great care is taken to choose the ideal plant. Common and Small Nettle are both used, for the Small Tortoiseshell has a strong preference for laying eggs on young, tender plants that are growing in full sunshine on the edge of large nettle beds.

Canon EOS 7D EF100mm f2.8 Macro USM – f8.0 / 1/250 / 100mm / ISO 400

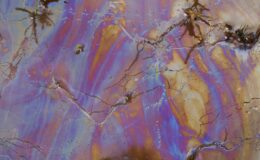

The camouflaged underwings resemble the colours and texture of bark and do a good job of concealing the Tortoiseshell when resting on a tree. However, against the bright green grass she is rather conspicuous and easy prey for birds.

Canon EOS 80D – Canon EF100-400mm IS II USM – f8.0 / 1/2500 / 400mm / ISO 1600

They will tolerate other males in the vicinity and will readily feed in pairs on the same plant.

Leave a Comment