On 13thMarch, I joined Megan Howells (People and Wildlife Officer) of the Wildlife Trust of South and West Wales, along with a small group of wildlife conservation volunteers, for what was to be the last work party before the corona virus lockdown. Obviously with the current Covid-19 measures in place, volunteering will not be continuing until those measures have been relaxed. We do not yet know how long this period will be, it could be until the end of April or it could extend to the end of May. It is therefore with a great deal of nostalgia that I look back to the last conservation work party, which happened to be a particularly memorable event.

Slow Worm (Anguis fragility) although superficially snake-like in appearance it is in fact a legless lizard. It is regularly found under refuges, often scrunched, concertina style into a ring.

Our task was to check the refuges at Parc Slip Nature Reserve and monitor any reptile or amphibian activity. Reptiles and amphibians are often thought of as being cold-blooded. This is not strictly true and a more accurate description would be ‘ectothermic’, i.e. relying on warmth from outside their body (by basking in the sun for example) to raise their temperature to a level that will enable them to be fully active.

Slow Worm hatchling showing the typical distinctive colouration; back light gold or silver with a distinctive black vertebral line; flanks and underside are jet black.

Reptiles – particularly snakes and slow worms – also raise their body temperature by sheltering under warm surfaces. A convenient survey technique is to place small sheets of corrugated iron partially exposed to the sun in areas where reptiles are suspected to be. It may take some time for snakes and slow worms to find them but, when they do, they will use them in a wide range of weather conditions from spring to autumn. As well as corrugated iron, materials such as carpet or roofing felt can also be used. Great care should be taken when positioning refuges to avoid exposing reptiles to risks such as crushing or collection. Each refuge should be carefully mapped and Megan Howells used a handheld GPS to carefully record their location so that they could be found again.

By turning over leaf litter or deliberately placed refuges, such as sheets of corrugated iron, planks of wood or old carpet, you never know what you may find! In this case the finger points to the droppings of a field vole. Such warm blooded mammals make tasty morsels for foraging adders.

If you intend to use refuges in a survey for reptiles there are some important considerations to take into account. For example, Adders often use refuges, and careless actions, such as lifting refuges by hand, without the aid of a stick, can result in being bitten. An Adder bite is serious and immediate medical attention should always be sought. The risk of being bitten is minimal if Adders are treated with respect and observed from a distance. Adders prey on warm-blooded mammals such as voles, mice and rats and have incredibly sensitive heat sensors located at the tips of their forked tongue, so it’s easy to see how a human hand can be mistaken for a tasty rodent.

Adder – Viperus berus – they like rough grasslands, heaths and moorland, but anywhere with sunny spots for basking, dense cover for shelter and plenty of prey – small mammals, on the whole.

Snakes such as the Adder are becoming increasingly endangered and are a UK BAP Priority Species. They must therefore not be disturbed and if approached should be done so with extreme care. For monitoring purposes this means that a member of the team must be a registered snake surveyor and have an appropriate licence.

Reptiles are secretive, highly camouflaged, unpredictable and generally do not assemble in one place to breed. This makes finding and recording reptiles more challenging than locating amphibians. Because reptiles are regarded as sun-loving, it might be imagined that they would be easiest to find in hot, sunny weather. In fact this is not the case, and the best conditions for finding reptiles are when the weather is cooler with hazy sunshine. An understanding of how reptiles behave in relation to weather conditions is perhaps the most important key to finding them.

The brown colouration and fatter appearance of this coiled up Adder is typical of a female.

All reptiles need to reach a specific body temperature to be fully active. For British species this is between 25 and 30C. The process by which a reptile achieves and subsequently maintains their required body temperature is called thermoregulation. Body temperature is raised primarily by basking in the sun, and some species will actually flatten their bodies in order to present a larger surface area to the rays of the sun. The Adder and the Common Lizard are both particularly efficient at thermoregulation, enabling them to inhabit areas north of the Arctic Circle. As well as basking, a reptile can also obtain the heat it needs from a source of retained heat, such as sun-warmed rocks or logs, or by sheltering under a surface that has been similarly warmed by the sun.

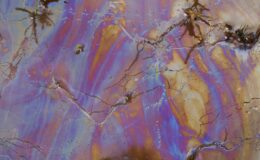

The red eye and vertical pupil along with the zig-zag dorsal pattern are typical characteristics of the Adder and make it easily distinguishable from the Grass and Smooth Snake (Britains only other indigenous snakes).

Once an individual has reached its necessary body temperature it will set off to hunt for food or to look for a mate. If, during these activities, body heat is lost, e.g. as a result of spending time in the shade, the animal will need to bask again to regain any lost body heat. The longer a reptile basks, the easier it is to observe them. The optional conditions are an air temperature of 9-18C, with hazy or intermittent sunshine and little or no breeze. Generally, the most likely times of the day for these conditions to occur are early to mid-morning or late afternoon.

A short, stocky snake with a distinct dark zig-zag dorsal pattern and often a row of dark spots along each flank. This is a female due to the dark brown markings against a light brown or straw-coloured background. In contrast, males typically have black markings against an off-white background with steel-grey underside.

Observation techniques

Reptiles typically bask on sunny slopes but close to cover into which they can retreat quickly. Some species position themselves so that they are partially covered by vegetation. It is helpful to know some of the preferences of individual species. For example, Common Lizards often bask on debris such as fallen logs that both retain heat and provide good exposure to the sun. The best strategy is to walk slowly and quietly with the sun behind you, and to examine potential basking spots (perhaps with binoculars) from a distance of at least three metres. If you hear a rustle as animal retreats into the undergrowth, mark or remember the spot, walk away immediately and return carefully after 10 minutes or so. As with dragonflies, I find that reptiles often return to the same spot to bask, or somewhere close by.

The Adder’s secretive nature and camouflaged markings mean it often goes unnoticed.

Looking for basking reptiles requires patience and practice. Don’t be disheartened by negative results and be prepared to make plenty of visits.

Why Record Reptiles and Amphibians?

Information about amphibian and reptile populations provides the basis for appropriate conservation action. All records, including those from gardens, will help build the detailed picture needed to ensure that viable populations of these creatures continue into the future. The National Amphibian and Reptile Recording Scheme (NARRS) is a programme designed to promote the monitoring of British reptiles and amphibians. Distribution data for these species can be found on the National Biodiversity Network website www.nbn.org.uk. To ensure that your records are included and to find out what information is needed to make a record, contact your local wildlife trust.

Britain’s only venomous snake which is inhabitant of open, predominantly dry habitats. Although good populations still exist on heathland and moorland nature reserves, the Adder has declined significantly in many places where it was previously common.

All images captured using a Canon EOS 7D and Sigma 150mm macro lens

With grateful acknowledgements to the Wildlife Trust of South and West Wales.

Leave a Comment