Cosmeston Lakes Country Park is a beautiful country park with lovely walks around the large lake. There is ample free parking at the entrance and it is, in general, a flat and pleasant walk around the park. The park opened to the public in 1978 and gained Local Nature Reserve status in May 2013. In the early 1980s (I forget the exact date) I was employed as part of a team of young labourers to generally look after the reserve. I therefore have a personal connection with the place and clearly remember the many trees that I planted. These trees are now well established, providing welcome shelters and homes to a plethora of wildlife. Conscious of the threat of increasing global warming, I like to think of these trees as my babies and I’m proud to have contributed a little towards conserving this beautiful environment. Today, there is an interesting medieval village next to the park. However, the main attraction remains that of being a haven for local wildlife. Along with Kenfig Nature Reserve and Parc Slip Nature Reserve, it continues to be one of my favourite places to visit, especially during the month of July – the perfect time to see dragonflies!

As I walk along the banks of Cosmeston Lakes, I usually pray for the weather to turn and allow at least a glimpse of the sun. I like to stop at a mud-dried bank and patiently wait for a Black-tailed Skimmer to appear. Characteristically these dragonflies are often seen perching horizontally on exposed surfaces, such as bare soil and mud, stones, gravel and dead wood. I’m therefore fairly confident that if I’m persistent and keep still long enough a skimmer will eventually appear.

Needing the heat of the sun to get airborne, Black-tailed Skippers are often seen resting on dried-mud banks or stony ground.

While waiting for dragonflies to emerge, I take the opportunity to watch the many types of waterfowl swimming on the calm surface of the lake. On this occasion, I was lucky enough to see a cormorant in the distance, precariously perching on some post while stretching his wings, as if to embrace the morning sun. I also caught a quick glance of a Small Grebe before it dived down, not to be seen again. The occasional coot would nonchalantly swim by, giving me a suspicious look before turning away in disgust. In contrast, a small group of young male Mallards seemed genuinely curious at my presence and inquisitively came to check me over. They were welcome and delightful company and didn’t seem at all bothered by my meddling. Neither were they camera-shy and seemed content to pose for my camera.

Cormorant stretching his wings as if to embrace the morning sun.

A curious young male Mallard inquisitively came to check me over.

While I enjoyed the wonderful wildlife around me, I couldn’t help but think that my main target species of the day remained stubbornly unseen. Until, that is, in a split second one turned, dashed and dived, grabbing a smaller creature in mid-air and despatching it with those tiny talons: as fine an example of hunting skills as you will ever find in nature. At last, the Black-tailed Skimmer had made an appearance, and oh boy, what a presence!

They are very aggressive towards other males and commonly perch on the ground or on low vegetation near the water margin from which they can scan a large area of water.

Black-tailed Skimmers are powerful predators and will eat insects as large as butterflies and smaller dragonflies such as darters, which they munch in flight or carry to a perch, grinding their way through their victim’s stiff exoskeleton with muscular, serrated mandibles.

Black-tailed Skimmers may attack smaller dragonflies, such as this dainty Ruddy Skipper.

As the morning turned to mid-day more males appeared and I watched them protect their territories aggressively from exposed perches, frequently flying out low over the water. The flight over water was rapid, just skimming the surface (hence the name ‘skimmer’), and jinking characteristically from side to side, with wings raised slightly in a shallow ‘V’. I didn’t observe any mating but I’ve witnessed it many times before, taking place in flight over water taking barely 30 seconds, although my field guide points out that otherwise it can last for up to 15 minutes. I did, however, witness egg laying – with eggs laid while in fight by the female dipping the tip of her abdomen into water, with the male hovering nearby.

Mature males acquire and retain territories along the pond bank.

These feisty dragonflies patrolled their airspace with all the zeal of First World War air aces. I watched them zigzag back and fourth, rarely rising more than a few inches above the water’s surface, and hardly ever landing. Just occasionally, I came across a Black-tailed Skimmer in a rare static pose. Needing the heat of the sun to get airborne, they perch on stony ground, or on the wooden slats of the boardwalks thoughtfully provided by the nature reserve.

Sandy ground provides a warm micro-climate and an ideal resting place.

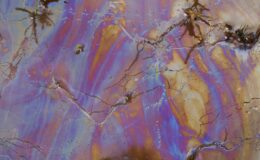

Moving carefully towards one, I took the opportunity to have a really close look: that broad abdomen, a delicate, powder-blue shade – almost mauve in some lights – and the lattice-like wings, held forward at an angle from the body, like a biplane about to run down the runway. Females and young males are very different in appearance: a wasp-like black and yellow, glinting in the early morning sun before they take flight once again.

Powerful muscles at the top of the thorax are needed in order to propel the dragonfly quickly into the air.

My 100mm macro and powerful 100-400mm telephoto lenses gave me access to a whole new world: from up close, I could see the tiny, downy hairs that cover the insect’s thorax. I took this opportunity to examine the structure of the dragonfly closely. They really are little miracles of nature: those dark green compound eyes, like something a sci-fi fantasy artist/writer would invent: It’s hardly surprising to note that H.R. Giger took his inspiration for his ‘Alien’ creature directly from the anatomy of the dragonfly. For example, the terrifying projectile mouth of a dragonfly nymph, Giger saw as a suitable proto-type for his Alien’s extending mouth.

Dark green compound eyes and powdery blue abdomen make this an attractive and distinctive dragonfly.

The segmented, long narrow abdomen is altogether a more aesthetically pleasing and less frightening part to observe than its tearing, serrated mandibles. It tapers evenly with males lacking the dark wing-bases of Scarce and Broad-bodied Chasers and having a longer and narrower abdomen. Yet the most beautiful and impressive anatomical part has to be the delicate-looking yet immensely strong wings, each latticed as if traced by a skilled etcher.

Delicate-looking yet immensely strong wings.

Looking more closely still, at the thorax, I noted that it was olive-brown with thin, incomplete black shoulder stripes. The wings – clear with a yellow costa and black wing-spots. In males the eyes are greenish-blue. The abdomen has a powder-blue pruinescence, except for the black base. In contrast the female has olive or brown eyes. The abdomen has two black stripes running down the tip, forming a ladder pattern; the ground colour is bright yellow. Like most insects, the females are far more illusive than the males and most often than not, they have eluded me although on this occasion I managed to take a picture of one (see below).

In females, the abdomen has two black stripes running down the tip, forming a ladder pattern; the ground colour is bright yellow.

Then without warning and before I could analyse it any further it took to the air and zoomed off, accelerating through the air at warp-speed, like the star ship Enterprise. Leaving me to ponder the thought that no description of the dragonfly’s physical form can do justice to the essence of its being. This quintessence of life is not mine to grasp nor frame, as if some Victorian connoisseur. The dragonflies belong to an altogether different realm and their kingdom is not of this earth. The poet Tennyson compared them to a living flash of light. Like the light of falling meteorites, living flashes of light that enlighten my spirit with a sense of awe and wonder.

Today I saw the dragon-fly

Come from the wells where he did lie.

An inner impulse rent the veil

Of his old husk: from head to tail

Came out clear plates of sapphire mail.

He dried his wings: like gauze they grew;

Thro’ crofts and pastures wet with dew

A living flash of light he flew.

Alfred Lord Tennyson

The Dragonfly (1833)

Leave a Comment