Whenever I visit Kenfig Nature Reserve’s waterlogged terrain during the early spring months, I’m reminded of Charles Darwin’s ‘primordial soup’ theory.

The theory suggests that life probably started in “some warm, little pond”:

“It is often said that all the conditions for the first production of a living organism are now present, which could ever have been present. But if (& oh what a big if) we could conceive in some warm little pond with all sorts of ammonia & phosphoric salts,—light, heat, electricity etc present, that a protein compound was chemically formed, ready to undergo still more complex changes, at the present day such matter would be instantly devoured, or absorbed, which would not have been the case before living creatures were formed.”

Letter to Joseph Hooker on February 1st, 1871.

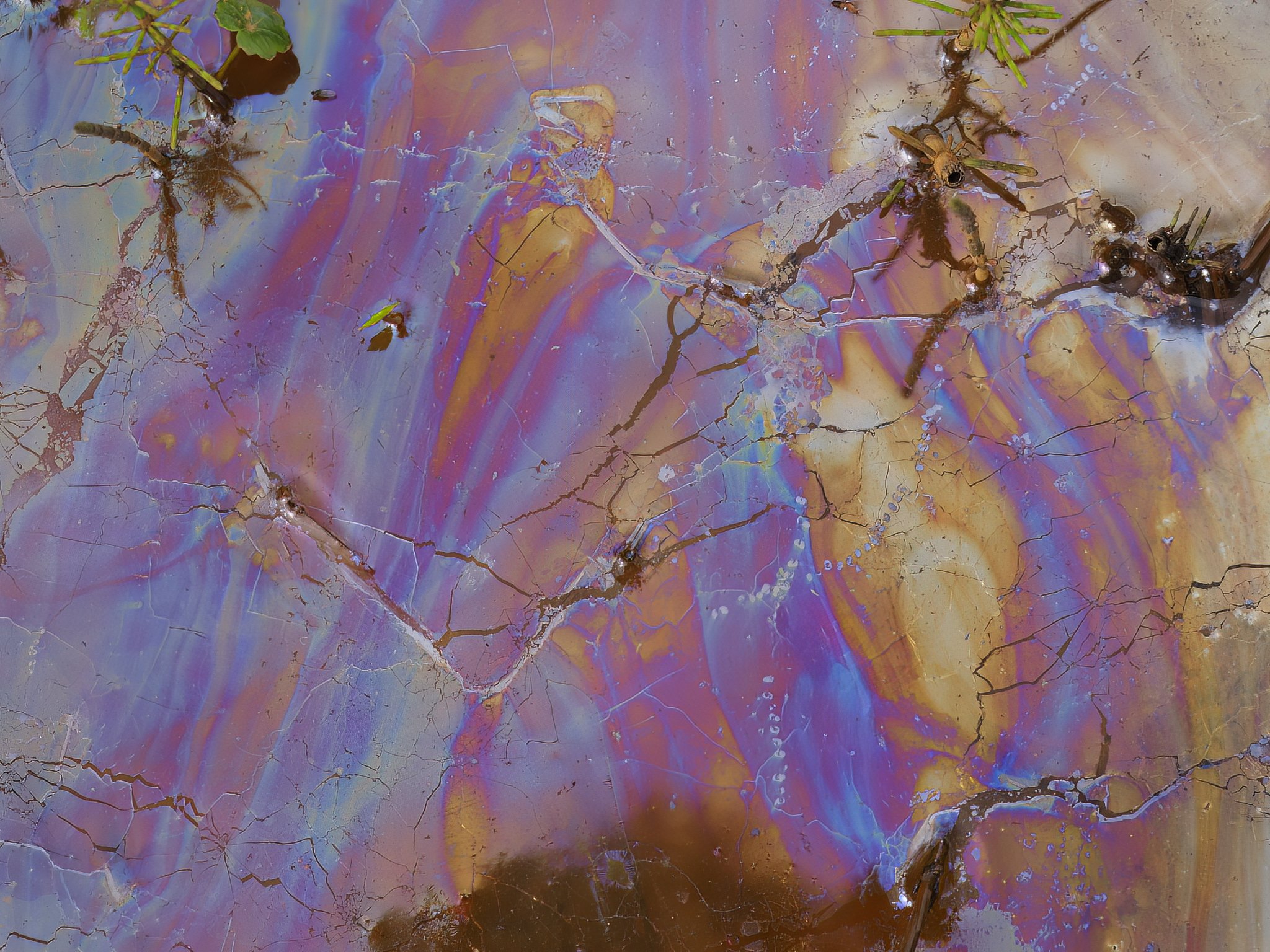

The silver, bubbling effect on the bog’s surface is the effect of a natural bacterial film, rich in organic matter.

Olympus 60mm f2.8 Macro on Olympus E-M1X – f5/6 / 1/500 / ISO 200

The bio-film is easily fractured, with cracks and bubbles appearing, as if rising from a living broth.

Olympus 60mm f2.8 Macro on Olympus E-M1X – f5/6 / 1/400 / ISO 200

The membranous surface present in such bog pools creates brilliant iridescent colours, rich in fractured textures.

Olympus 60mm f2.8 Macro on Olympus E-M1X – f5/6 / 1/320 / ISO 200

There are some key factors in Darwin’s observation that scientists now believe are critical for a successful primordial soup. In a crux, it means that a primordial soup with all the same ingredients like different amino acids and electrolytes will respond very differently to sunlight on a small pond than verses a large ocean. Pools on land can periodically dry out almost entirely when it gets hot, then fill up again when it rains. Such wet-dry cycles may seem innocuous, but they can have profound effects on the chemicals of life.

Pools on land can periodically dry out almost entirely when it gets hot, then fill up again when it rains. Such wet-dry cycles may seem innocuous, but they can have profound effects on the chemicals of life.

Olympus 12-40mm f2.8 on Olympus E-M1 MarkII – 12mm / f8.0 / 1/20 / ISO 200

On the heathland margins of Kenfig Pool, colonial trees, such as this Silver Birch, will eventually take over.

Olympus 12-40mm f2.8 0n Olympus E-M1 MarkII – 12mm / f5.6 / 1/200 / ISO 200

Can we not imagine that primordial soups, similar to the type that Darwin alluded to, exist today in the transient peaty landscapes referred to as Carr? In such habitats, the soil rises above the water level, allowing scrub and trees such as Willow and Alder to colonise. Such colonisation of new plants sustains a rich biomorphic eco-system of living organisms. The membranous surface present in such bog pools creates brilliant iridescent colours, rich in fractured textures. Brake the surface and fractures, cracks and bubbles appear, as if rising from a living broth.

Primordial soups, similar to the type that Darwin alluded to, exist today in the transient peaty landscapes referred to as Carr.

Olympus 12-40mm f2.8 on Olympus E-M1 Mark II – 12mm / f8.0 / 1/40 / ISO 200

Colonisation of new plants sustains a rich biomorphic eco-system of living organisms.

Olympus 12-40mm f2.8 on Olympus E-M1 Mark II – 12 mm / f5.6 / 1/80 / ISO 200

The margins of Kenfig Pool provide a location where one can observe the progression of vegetation, starting from a terrain submerged by fresh water, as one stage in a hydrosere. The low lying dune slacks also contribute to flooding, but as they gradually dry out in the summer, a special and rare plant community grows which includes many orchids. People travel from far and wide to see Kenfig’s slacks, and we probably have the wettest and largest area of slacks in the UK. Their flatness looks somewhat un-natural but humans have had nothing to do with creating their profile. During periods of high sand mobility in the past, wind would have blown dry sand downwind, gradually lowering the ground level until the water table was reached. Wind cannot move damp sand, so the base of the slack surface matched the flat water table. As the water table rises during the winter, the slacks flood. The slacks are particularly wet at Kenfig, because a layer of boulder clay beneath the sand prevents ground water from being lost into the ground below. Instead, the water table rises and slowly seeps through the sand off the dune system and into the River Kenfig to the north and onto Sker Beach to the west.

Early -Puple Orchid – Orchis Mascula

The low lying dune slacks also contribute to flooding, but as they gradually dry out in the summer, a special and rare plant community grows which includes many orchids.

Olympus 60mm f2.8 Macro on Olympus E-M1X – f2.8 / 1/1600 / ISO 200

March Marigold – Caltha Pafustris

The glossy yellow flowers, also known as King Cups, thrives in such wet habitats.

Olympus 12-40mm f.2.8 / 12mm / f8.0 / 1/50 / ISO 200

Cuckooflower – Cardamine Pratensis

The beautiful, delicate pink flowers, also known as ‘Our Lady’s Smock’ thrives in damp meadows and is a sure sign that Spring has arrived.

Olympus 60mm f2.8 Macro on Olympus E-M1X – f4.0 / 1/400 / ISO 200

Newly formed slacks comprise bare damp sand with a few specialised plants which can colonise and survive in the difficult growing conditions. With time, more plants can grow as a thin soil slowly develops. Eventually, a thick covering of vegetation forms and wetland trees such as willows, alder and birches take over. And all this natural variety develops, in no small measure, because of the carrs, bog pools, dune slacks and pockets of primordial-like soup that swamp the landscape.

Hanging from moss covered branches, ferns gracefully hang, backlit and glowing, appearing transparent against the bright, dazzling sunlight. Their spores are clearly visible on underside of leaf – (see next image.)

Olympus 60mm f2.8 Macro on Olympus E-M1X – f2.8 / 1/800 ISO 200

Ferns reproduce through their spores. Spores are tiny, genetic bases for new plants. They are found contained in a casing, called sporangia, and grouped in bunches, called sori, , on the undersides of the leaves.

Olympus 60mm f2.8 Macro on Olympus E-M1X – f5.6 / 1/30 / ISO 400 – stack of 15 images

Leave a Comment